What is a plot?

Just in case we needed that clarifying.

Plots are things we make every day, whether when we're on our way to work and contemplating how the day will go, or in the shower and having those imaginary arguments with people. They rarely have any great meaning to them, let alone a beginning, middle, and end, but it doesn't mean we're not already very familiar with the idea of how they're made.

For a writer, plots tend to be what we try to jot down in order for us to organise our thoughts. A scene here, a line of dialogue there, and I'd put money on most of these 'plots' being abandoned.

To some, this may be the visual representation of a plot

In reality, a plot can look like anything, and there isn't a 'winning' rule for a great plot.

In my opinion, a plot needs only three things.

- A beginning

- A middle

- An ending.

everything else is just whistles and bells.

What should a plot be?

|

| Plot |

Like I said before, most plots are discarded long before they're ever completed. Some people write an entire plot for just one scene, developing a moment in so much detail that they lose the... plot...

They're basically so lost in that scene that the rest of the story becomes unobtainable. This can lead to a form of 'writer's block' where the writer has dug down so far to isolate this one gem of a scene that they find it hard to climb back out.

What you should be aiming for with a plot is a guideline of 'plot points'. It needs to read like an instruction manual for any keen writer's manuscript, for the writer to refer back to REGULARLY, to update, adapt, and mark off when scenes have been reached.

Due to this, a plot should be briefly and clearly stated. Broken down, it means

- Succinct

- Straight Forward

- Simple

Anything more complicated than this and you'll have lost the use of a good plot outline.

Why does it matter to plot out your manuscript?

I suppose it doesn't, really. To each their own. But ask yourself this, how many times have you been in the throes of writing and, suddenly, you're stuck! You might have a general idea of where you want to go, but you're missing vital scenes on how to reach that point. This likely happened because you haven't followed a proper plot outline, to which this blog might help.

The benefits of a plot outline

In brief, it helps you keep your story flowing.

Exposition is the biggest killer of a story's flow. How often have you read a book and suddenly stopped to think 'jeez there's a lot of explaining in this'. I found it happened quite a lot in the Harry Potter and Twilight series, where rather than having the time to show us, the author used the characters to tell us. It makes sense in the end, because the books would be ridiculously long if they showed you everything. So, at times, they have to tell us someones background, or describe an event to us. But this tends to be boring for the reader, even if it is crucial.

Because of this, exposition should be treated like medicine; tightly regulated and properly administered.

If you need to tell the reader a character's background, do it when it's relevant. Don't lump it into the beginning of the book if you don't need to, choose a scene before a dramatic event (never during! Never EVER put exposition into a dramatic scene, it destroys the energy completely) because this way you're rewarding the reader with some juicy action.

By putting these exposition points into your plot, you can move some exposition around if that chapter or area gets a bit expo-heavy. It takes practice, but once you can 'see' it, you can work it.

Starting a plot outline

Bullet points.

These things. 🢚 • 🢘

Ok?

Not paragraphs. Not textwalls. Not diagrams.

Bullet points.

See below.

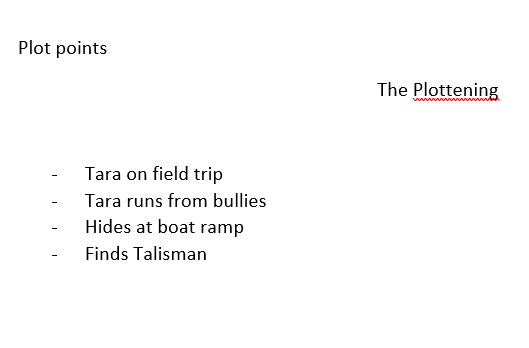

Making a Plot Step 1

This means nothing to you now, and that's how it should be, because stage one is the most simple it should ever look. But to me it speaks volumes. So how do you achieve this?

Basically your goal is NOT to tell yourself the story. You're not writing a novel here. Instead, what you're doing is breaking your story into scenes, giving each scene a title, and then writing those titles down into bullet points.

The aim of the game is to be able to look at the title of each bullet point and KNOW in your mind what that scene is. Sometimes, this isn't achievable straight away. Sometimes, you have to go to your scrapbook/word document and write it out, play around with it, and make it a memory, before coming back to your plot and writing it in.

And that's the important part.

COME BACK TO YOUR PLOT.

When you open your WIP, make sure you open your plot, too!

I, personally, keep my plot in Onenote, and my WIP in Word. Then I can Shift Tab between them easier.

I went off on a tangent. Back to making a plot Step 1.

Do this method until you get to the very end of your WIP. I know it might be hard because you're probably thinking 'but I don't have an ending yet' or maybe not a middle or a beginning if you're someone who has random parts of the plot first.

Don't fall for it! Remember what I said about focusing too much on one scene that it blinds you to the rest of the path? The point of this plot is to push you through to the end. Do not start expanding your plot until you've reached the end, even if that means going to the drawing board and continuing to work on ideas.

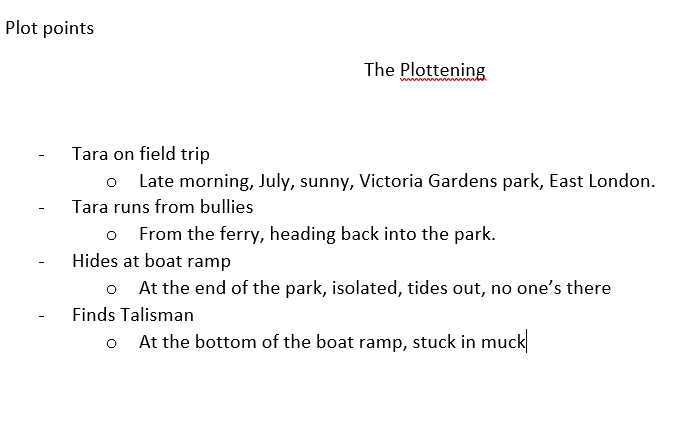

Making a Plot Step 2

So, you've reached the end of the initial plotting process, with several sheets of bullet points and the scene titles? You know you've nailed it when you can look over each title and know what that scene means. So what's next?

More bullet points.

Specifically, adding important information relevant to that scene.

Step 2 is far more crucial than most realise, but not because it's important to the flow of the story, but more so the continuity. It's easy to forget what day that scene falls on, where it's occurring, who's there, and other important factors like festive dates or relevant points in history.

If you're like me and like to keep track of how many days have passed between each scene, or if you have flashbacks, this is also great to put into these second sets of bullet points.

Again, simplicity is key!

You don't want to be telling ANY of the story with these bullet points. It's literally on a need to know basis.

It's easy to fall into 'writer mode' when filling these out, but try to pretend that each word costs you a dollar/pound, and you're saving for a takeaway.

Again, continue this step until you get to the end of the book! Even if you have to skip some parts that you can fill in later.

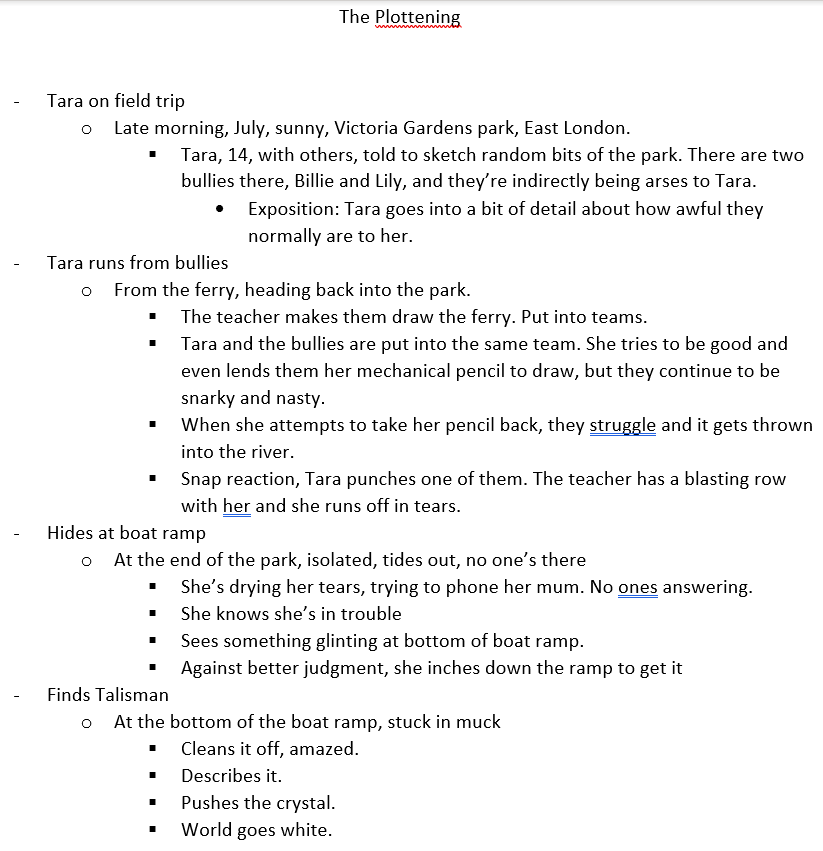

Making a Plot Step 3

Now THIS is what I'm talking about.

Here's the meat of it. The next set of bullet points are used for you to finally get the story across. BUT, and I can see you're salivating at the idea of writing the scenes out like Stephen King on drugs. No! Stop. It ain't hammer time. You need to conserve space and make it as simple as you can.

Again, my plot points won't mean all that much to you, but when I scan through these, I know that when Tara's drying her tears, she's doing it on the inside of her school jumper as she sits in the shadows of the flats overlooking the boat ramp going down to the Thames riverbed. I don't NEED to tell myself that again because I already know it.

And that's the problem a lot of people get into when writing their plots. They're telling themselves things they already know.

Your main character has a scar over his brow that burns when he thinks of how his parents died? Great, you know this, so don't write it in detail. You're BF has a horrific fever and you love him so much that you'd risk getting killed by other murderous contestants to find him a cure? That's awesome, but don't write it out as if you're selling this to Scholastic.

The aim of the game is to glance down the titles and know what it means. If this doesn't work, it means that scene isn't working, and you need to work on that little bit back in your scrapbook/document.

Making a Plot Step 4

Step 4 could mean making another set of bullet points so you can actually flesh out more of the story. this isn't illegal. The Gestapo won't take your family to a gulag for doing this and, if anything, at this stage I encourage it! Especially when it comes to that dreaded 'Pill of Exposition'. In these bullet points, you can say

"This might be a good time to let the reader know that Lyra has a fear of losing her demon, because several chapters on from this, she's faced with losing Pan!"

That has allowed you to drop the exposition in, for the reader to unconsciously digest it, and to make for a bigger impact when that dramatic scene comes about!

It also allows you to move scenes around easier, or remove them completely, or add bits in between. The amount of organisation you put into these four steps will reduce the amount of brainpower you'll need when actually writing it.

In closing

Sweat over the plot so you don't need to sweat over the story.

Flow is the biggest killer of any book, and plots allow you to see how much action you have compared to exposition.

Edit your plots! Sometimes we HAVE to write scene titles out with a bit of information. Or we write them out with a lot of flesh so we know where we're at. Go back over these and cut them down. Remember, you're saving for that kebab.

the more you can get across with the least said, the better your plot will be.

This means over half the work is done by the time you write that fateful, 'Chapter One, in the beginning' and will stop you hitting dead ends and false turns as you go.

Thanks for reading. I hope this helped. Catch me at @DangelAngello on twitter and keep writing.